By Trent Lakey

The inimitable Diane Keaton, one of American cinema’s greatest icons, passed away last year at the age of 79. For decades, beginning with The Godfather in 1972, she brought warm, witty, wounded and romantic performances to the screen, with an idiosyncratic presence that filled every frame she occupied. She was best known for her role in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, along with seven additional collaborations with him, and became embedded in ’70s culture: Her tomboyish wardrobe, charm and spirited intellect established a new kind of screen actress. Like the greatest movie stars of the New Hollywood era, she seemed to emerge from the same cultural force that inspired the masterpieces of the day. In 1977, in particular, she became an emblem of a changing culture.

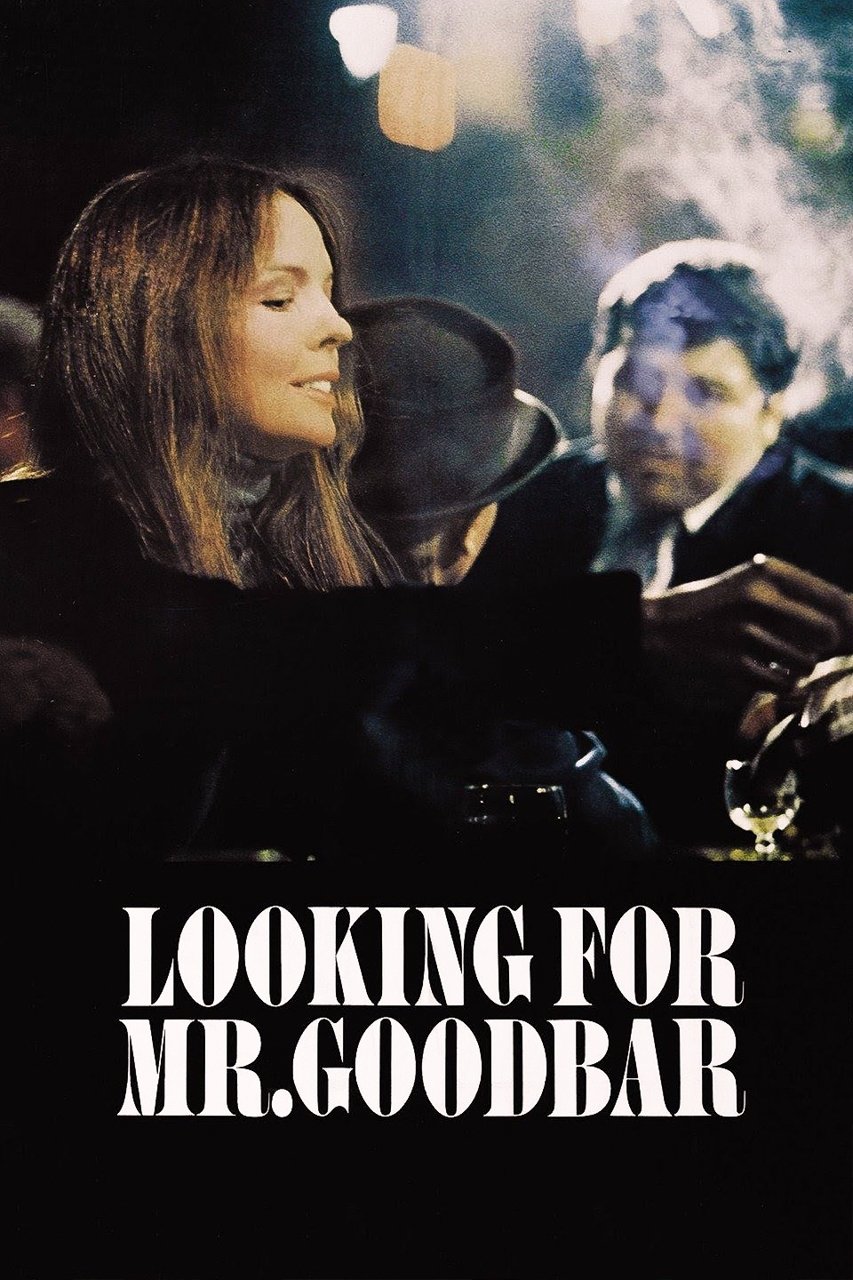

Keaton won the Oscar for best actress for her turn as the ditzy Annie Hall, yet she delivered another lauded performance in 1977 that, while not recognized, may have bolstered her case for the award. The film was Looking for Mr. Goodbar, directed by Richard Brooks (known for acclaimed literary adaptations such as Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Elmer Gantry) and adapted from the bestselling novel by Judith Rossner. The film follows Keaton as Theresa, a schoolteacher who teaches deaf children by day and spends her evenings pursuing sexual encounters with strangers she meets in bars and nightclubs. Her trysts, while initially steeped in the exhilarating liberation of intimacy, grow increasingly hostile as her lovers attempt to control or possess her, leading ultimately to violence and tragedy.

In Annie Hall and Looking for Mr. Goodbar, two diametrically opposed films with the same graceful woman at their center, Keaton’s range — from tragedy to comedy, from love to death and everything in between — was on full display. It has been speculated that the strength of both performances contributed to to her Oscar win for Annie Hall. It is not hard to see why: Both are distinguished, subtly melancholic and marked by a personal freedom in each character’s highest moments that is infectious and undeniable. It was her moment, often the decisive factor in an Oscar victory.

Yet her work in Looking for Mr. Goodbar retains significance apart from golden statuettes (as do most films, but I digress). It offered a convincing portrayal of a liberated woman and the reactionary men who surrounded her. Keaton’s character seeks refuge from a painful past, a cloistered family life and a lonely existence in the perspiring, transient arms of intimacy. She flees the influence of her dogmatic Catholic father only to encounter lonely, libidinous men with dogmas of their own, rooted in pervading masculinity. While this tragic core drives the film, Keaton’s performance — as a woman whose self-discovery is cut short — ranks among her finest and encapsulates all that made her such a singular and compelling screen presence.