By Travis Mullis

If cinema were a dinner party, Annie Hall would be the guest who arrives late, apologizes profusely, then spends the evening explaining why everyone else’s neuroses are more interesting than his own. Woody Allen’s 1977 masterpiece is often called a romantic comedy, but that’s like calling Proust a diarist — it’s technically true, but it misses the point. This is a film about the impossibility of happiness, rendered with such wit that you almost forget it’s breaking your heart.

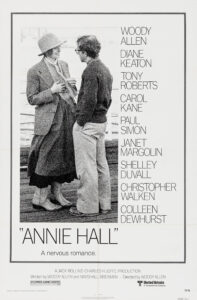

Allen’s alter ego, Alvy Singer, is a man who treats life as a series of footnotes to a joke he hasn’t quite finished writing. His relationship with Annie — played by Diane Keaton with a distracted luminosity — is less a love affair than a philosophical experiment. Can two people connect when one of them is allergic to joy and the other thinks “la-di-da” is a worldview? The answer, of course, is no. But what a glorious failure it is.

The film’s genius lies in its structure: flashbacks, split screens, subtitles revealing thoughts that should never be spoken aloud. Allen doesn’t just break the fourth wall; he demolishes it and builds a lecture hall in its place. Yet for all its intellectual scaffolding, Annie Hall is never cold. It’s warm, funny and painfully accurate about the way relationships collapse — not with a bang, but with a shrug and a nervous laugh.

The film’s genius lies in its structure: flashbacks, split screens, subtitles revealing thoughts that should never be spoken aloud. Allen doesn’t just break the fourth wall; he demolishes it and builds a lecture hall in its place. Yet for all its intellectual scaffolding, Annie Hall is never cold. It’s warm, funny and painfully accurate about the way relationships collapse — not with a bang, but with a shrug and a nervous laugh.

Beneath the jokes about death and lobster pots is a simple truth: Love is fleeting, memory is unreliable, and the best we can do is turn our failures into art. On that score, Annie Hall succeeds magnificently.

But Annie Hall didn’t just succeed; it changed the game. Before Allen’s intervention, romantic comedies were glossy affairs with predictable arcs. He shattered that template by making the story fragmented, neurotic and self-aware. The film’s nonlinear structure, direct-to-camera monologues and surreal flourishes (like Marshall McLuhan appearing in a movie line) became hallmarks of “smart” cinema. It proved that audiences could handle complexity and humor in the same breath.

Allen’s persona — intellectual, anxious, self-deprecating — became a cultural archetype. Suddenly, neurosis was fashionable. His blend of psychoanalysis, existential dread and Jewish humor influenced everything from sitcoms (Seinfeld owes him a debt) to indie films. The idea that vulnerability and wit could coexist in a leading man was revolutionary.

And then there was Diane Keaton. Her wardrobe — oversized blazers, men’s ties, floppy hats — sparked a fashion movement. It wasn’t just a costume; it was a manifesto of individuality. Women embraced the androgynous, layered style as a rejection of rigid femininity.

The film also injected phrases like “la-di-da” into the lexicon and normalized intellectual banter in mainstream cinema. Its jokes about Bergman, Freud and New York neurosis made cultural literacy feel sexy. It helped cement Manhattan as the cinematic capital of wit and angst.

Directors such as Noah Baumbach, Greta Gerwig and Richard Linklater owe a creative debt to Annie Hall. The film’s conversational tone and episodic structure became a blueprint for indie storytelling. And its central thesis — that love often fails despite our best intentions — felt radical in 1977 and remains painfully relevant. The film anticipated the modern dilemma: We’re more self-aware than ever, yet no closer to happiness.

Annie Hall is not just a film; it’s a cultural landmark. It taught us that comedy could be cerebral without losing its heart, that fashion could be philosophy, and that failure — rendered with honesty and wit — could be beautiful.