By Trent Lakey

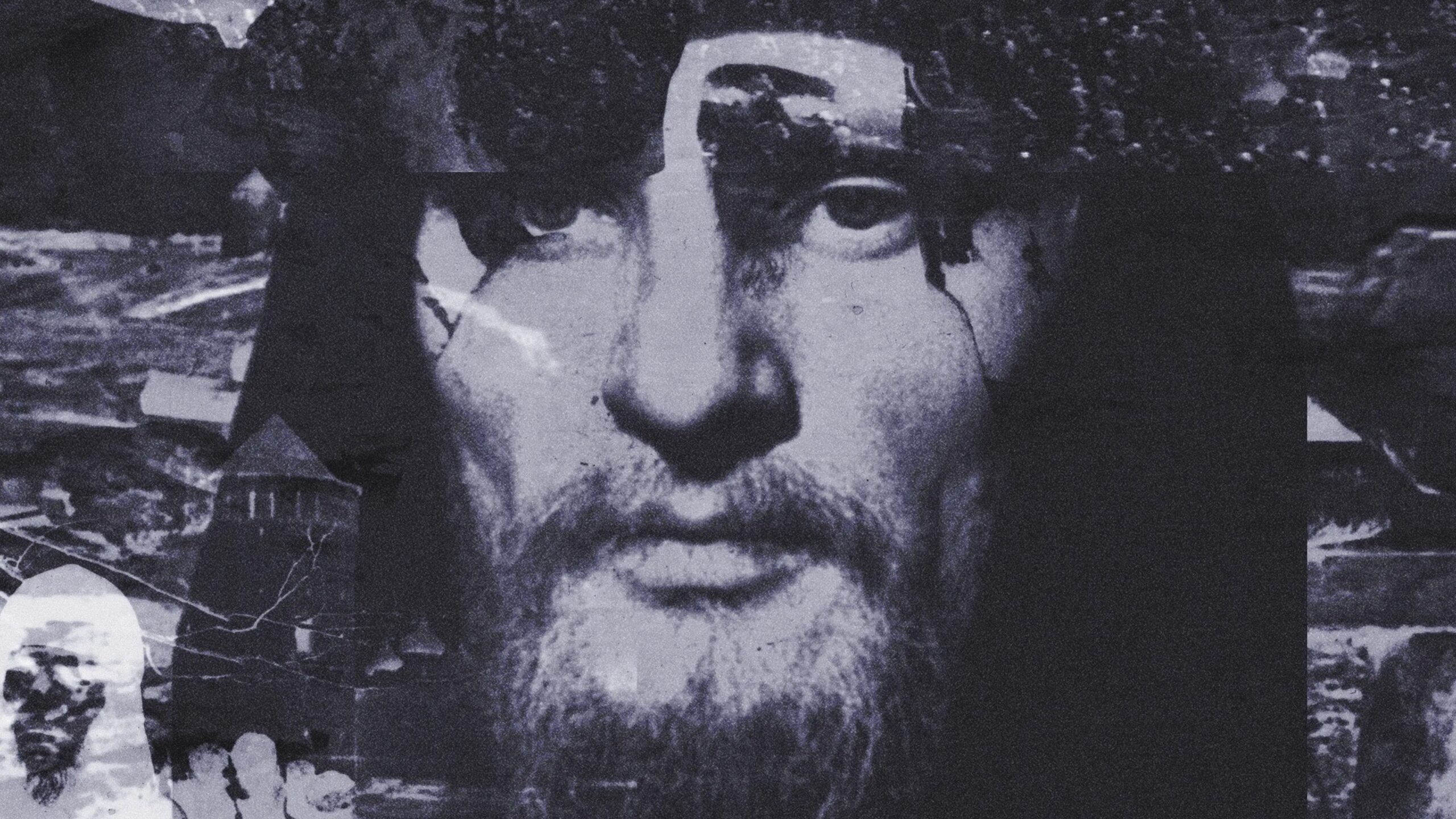

A jester stands achingly alone in the rain. Milk spills into a river, falling from the hand of a dead man. Snow begins to fall above a cathedral filled with debris and corpses, as smoke rises to meet the snow. Such is a sample of the indelible images in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, which follows a Russian icon painter through his tumultuous life in the 15th century.

The film first screened in the Soviet Union in 1966 but was long censored at home and abroad for its supposed bleak portrayal of Russian history and its experimental narrative and form. The ban was later lifted, and in 1969 the film premiered to great acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival, where it played out of competition but won an award from international film critics. Only Tarkovsky’s second film — his first, Ivan’s Childhood, won the Golden Lion, the highest prize given at the Venice Film Festival, in 1962 — Andrei Rublev has since become regarded as one of cinema’s great achievements.

Tarkovsky believed in a cinema of poetry: uncommercial, built on the artist’s ideal, and rooted in the poetic associations that came with it. He believed this cinema would break down the barrier between art and viewer, stirring the innermost recesses of the soul into contemplation and preparation for the supreme things of life: love, faith, and death. Watching a Tarkovsky film is perhaps closer to experiencing one man’s vision of the divine’s place on earth than to entertainment. It is not without entertainment and intrigue, but that is not his goal.

The film unfolds in a fragmented structure, presenting eight episodes in the life of Andrei Rublev, from his apprenticeship in a monastery to his old age and final works. Tarkovsky is less interested in biography or historical record than in portraying the imperfect world from which Rublev’s art emerged.

Rublev’s aim in painting is perhaps the same as Tarkovsky’s in film: to present the ideal beauty of the artist, shaped in an often ugly and cruel world. For Rublev, that ideal lies in the face of God. Tarkovsky’s is less defined; his God moves through wind and rain, the faces of strangers and the falling of snow. His faith is in the potential within each person for love and purity, but he is not naive enough to believe it can be achieved. That is why it exists in his films and not in the world.

That is the capacity for art in Tarkovsky’s time, in Rublev’s and in our own. By the end, after the barbaric events and cruelties inflicted on innocent Russians of the 15th century, it is the art that remains, engendering a great feeling of awe in the viewer and giving one something to believe in, even if it is not always understood.

A new restoration of Andrei Rublev will screen at IPH Aug. 16–19.