By Ryan Thomas

If you’ve never seen a Robert Altman movie, shame on you: Go watch The Long Goodbye, California Split, Short Cuts, The Player, Secret Honor, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Popeye, 3 Women and A Prairie Home Companion. But also understand that Robert Altman movies are watched, not heard; sketched, not blueprinted; felt, not understood. He’s not for everybody.

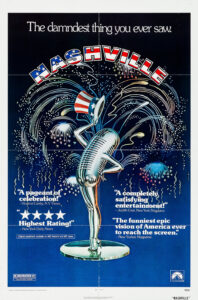

Every Altman film is a satire, and so is Nashville, which will start screening Feb. 20 as part of IPH’s Centennial Icons series. Probably no one was better suited to direct a three-hour sendup of country music, American politics and the human condition than Altman was in 1975. It’s duly seen as his masterpiece. But that’s because Nashville is also soft and gentle, quietly desperate, bittersweet and deeply sad. It is stories of wannabe stars and washed-up fogies, go-betweens and hangers-on, people in it and around it, all falling in and out of love, a tapestry of ambition and Americana.

Altman’s movies are shambling, shuffling and incoherent as often as they are transcendent. Scripts were suggestions. Swaths of his movies are improvised. In Nashville, most of the songs were written by the actors singing them. The man never cared. Usually he’d come to set late, stoned or hungover or some combination of the three and tell the actors to do it again, make something up, play with it, make it their own. They’d do it and do it again, and before you knew it, they were moving on, next setup, next scene. A few swore never to return; most loved him forever.

The editing room was where Altman did his work. Nashville crosscuts between 24 characters and almost as many storylines, but you’re never lost, bored or ahead of the movie. Short Cuts, based on nine Raymond Carver stories and a poem, is the same. For someone who ignored (and defied) screenwriters as much as he did, Altman had an innate understanding of narrative. It almost always worked out in the end, no crossed fingers needed.

No one inspired the critical adoration and annoyance that Altman did either. (Having Pauline Kael in the former camp helped.) The movies either hit you or they didn’t, and that was your problem, not his. It’s proof that there are as many ways to make a great film as there are great filmmakers. “If I made a film that everybody liked,” he said in 2001, “it would be pretty terrible.”

This year is Nashville’s 50th anniversary, and Altman’s 100th. He was born in 1925 and spent time in the Pacific Theater and the actual theater before directing M*A*S*H in 1970. He basically reinvented cinema and had one of the greatest decades in filmmaking history, becoming Hollywood’s middle-aged voice of the counterculture. Then Popeye flopped in 1980, and he flittered in and out of relevance, movies, TV and plays, always working, never not. Your problem, not his.

He died at 81; only the movies keep living and breathing. You can see them in Paul Thomas Anderson, Richard Linklater and the Safdie brothers. You can see them when a director goes to war for his movie with a studio executive. And you can see them in movies about people, not characters, and in movies that are funny and sad and everything in between, like Nashville. He must have done something right to last 100 years.